Fads and Fallacies: Modelling Fashion

5 Minute Read

This article is one of a series of articles from Metalsmith Magazine "Fads and Fallacies". For this 1989 Summer, A. Stiletto talks about modelling fashion and the essential relationship between jewelry and the wearer.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

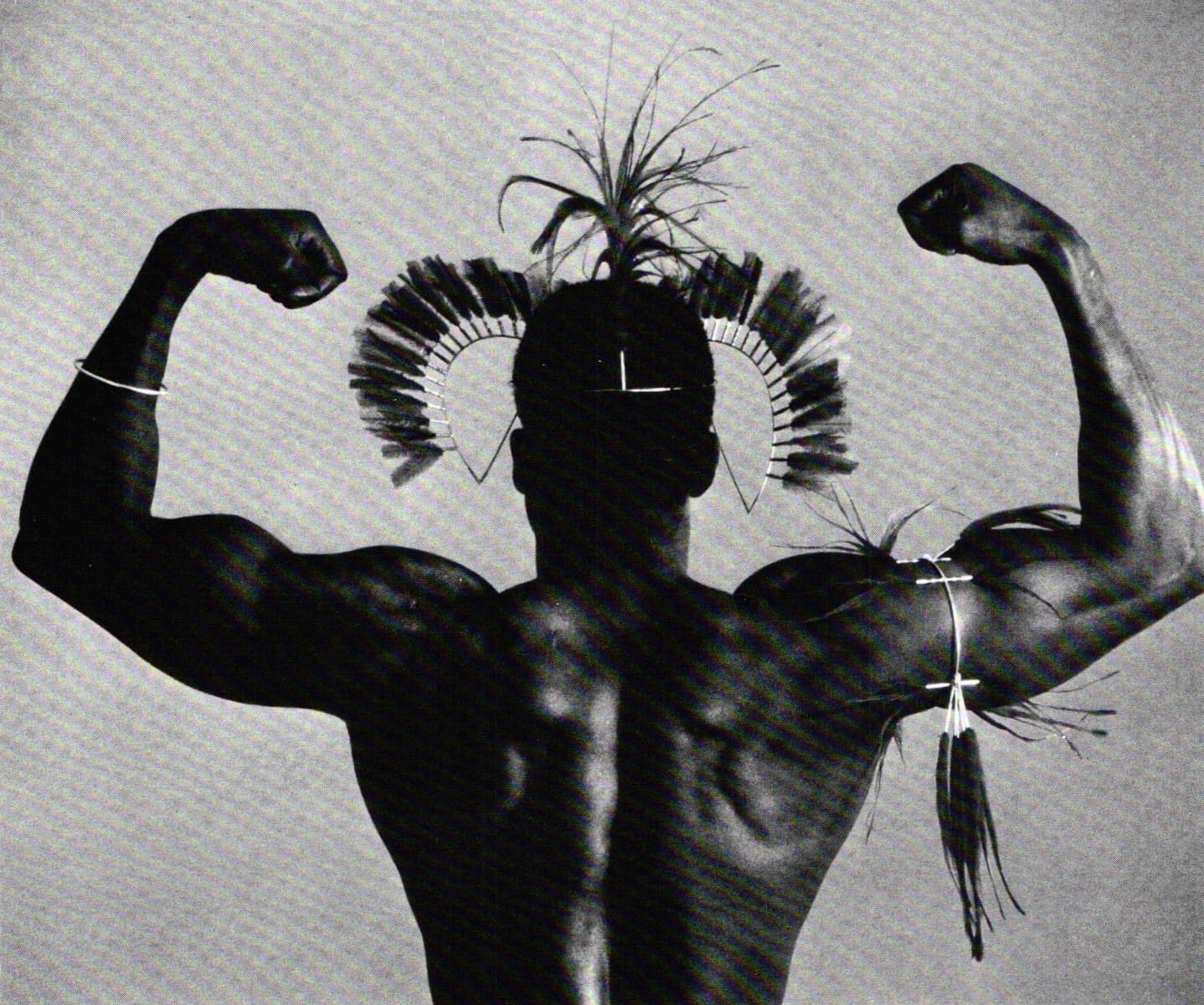

The model is essential to fashion. It is a commonly held belief that adornment cannot be properly appreciated without that something or someone to be adorned. Isolating clothes or jewelry from the wearer leaves an aura of sterility that renders them impotent. Clothes might be examined on a rack in a department store or jewelry in a display case, but there is always the assumption that we are looking at them as if they were on some body and, in fact, we fulfill that vision by eventually trying them on.

This relationship between fashion and the wearer poses a fundamental problem for the designer. Logically, it is impossible to design adornment for everyone, to create a universal solution to the problem of individual taste while at the same time claiming that when the wearer tries on the design, it becomes his and his alone—viz, "that's really you!"

Fashion has therefore adopted the convention of the model, in its inanimate form—the mannequin—or, in its static, two-dimensional form—the fashion photograph—as surrogate for the wearer. What is at work in these conventions, however, is a distorted projection of reality, an Alice-through-the-looking glass fantasy world. This narcissistic mirror of fashion often looms so seductively that we can't help but want to experience its glamour by wearing the depicted accoutrements.

The use of a normative model by fashion is a well-conceived device for suspending the wearer's belief in him/herself. When we look into the mirror of fashion, we don't see ourselves, we see what the designer would like us to see. When we try on the designer's work, we don't see ourselves, we see a celebrity of the designer's making.

The fashion designer cannot function without an intermediary model, he must redirect the wearer's attention away from selfish interests and towards his own creation. By packaging the wearer's personality, the designer encourages the wearer to respond to the stimulus of a "look," a tacit set of visual signs that conditions the wearer to know what he likes rather than like what he knows. The danger exists when the designer's goal becomes the manipulation of the wearer's sense of himself/herself, to the extent that the wearer is viewed as mechanically robotic, devoid of ego and will. Often the faint cries of "victims of fashion are the reaction to this growing strength of fashion's psychology of the transference.

However, the use of a surrogate (mannequin. model or photo) is not totally inimical to artful portraiture. In the myth, Pygmalion carved an ivory statue of a maiden and fell in love with it. In answer to his prayers, the goddess Aphrodite brought it to life. But there is a major difference between sculptural portrayal and a commercial model. We see sculpture as an abstract symbol of our humanity, not toying with our self-image but as some essence of our culture's collective nature. On second thought, maybe fashion is like art, if we consider both to be attempts at creating a universal image that we all can relate to, hoping, like Pygmalion, that the image will "come alive."

I am thinking here about another instance of fashion—objects such as cars and furniture that don't employ the body-model as a strategy but do employ a similar psychology. Here designers imbue their products with a "sense of themselves" that they hope will be appreciated by their audience, who also have a similar "sense of themselves." lf their strategy is successful, the consumer will feel that some of the values the maker exhibits in his product correspond to their own values.

But I am still troubled by the analog, of these objects with clothes or jewelry. In the former, the integrity of the maker object and user is maintained, each with a distinct personality. In the latter there is an implied notion that the object "changes" the user's physical countenance or psychic self-appraisal. Also, these objects (cars, furniture, etc.) don't in themselves change when they are appropriated by the user, unlike the way changes are claimed to occur with clothes and jewelry when they are worn. Jewelers I know say that this question of relating to an artist's esthetic, and transfiguring the wearer inevitably centers around the role of the body. They still define jewelry as that which is physically and psychologically, worn.

I would argue that citing the "physical" condition is lame. I realize that jewelry must be of a weight, size and configuration that rakes into consideration human anatomy, but there is no mystery in this—the human body essentially comes in standard models. Ergonomically (that is. the understanding of the way the body finds comfort in the physical world), most of the problems have been worked out by science.

This leaves me with only the psychological relationship of jewelry, whether the viewer appreciates the designer's jewelry, because of an empathy with the esthetic or because he sees himself changed by the jewelry once worn better stated, whether the jewelry "looks good" or whether the wearer looks good when the jewelry is worn. Can it be that jewelry can be "bad" simply because it is worn by the wrong person? Doesn't this place an inordinate value on the wearer in completing an esthetic object? Appreciation confused with creation?

Practically speaking, I have never seen a jeweler laboratory-test jewelry for the ideal subject or wearer, trying to determine the right psychological makeup of the individual to complete the artist's vision. Jewelers work in privacy with their own esthetic and without foreknowledge of the wearer. Sure, there is the matter of context, paintings go on the wall, jewelry on the body. But there is a distinction between the body as context for jewelry and the proscription of the body as model for fashion.

The tug-of-war between the jewelry esthetic as that of the wearer or that of the maker is a healthy one of interpretation and intention, but if it might resolve itself potentially in a "model" wearer, in some agreed-upon image of personality, then the function of jewelry must be questioned. If the jeweler is intent on claiming the body for jewelry, does he not rob the wearer is asked to be complicit with jeweler's profile, does not jewelry tread dangerously close to propaganda?

A. Stiletto works in and around New York and writes a regular column on fashion for Metalsmith.