Emergence of Modern Jewelry

The Jewelry Museum of Pforzheim possesses one of the most remarkable collections of modern jewelry. This exhibition of works, which is divided into four decades, offers a captivating view of the emergence and development of an entirely new jewelry philosophy. Its way paved by a few forerunners, this philosophy has now taken hold worldwide among the avant-garde in the world of jewelry.

4 Minute Read

The Jewelry Museum of Pforzheim possesses one of the most remarkable collections of modern jewelry. This exhibition of works, which is divided into four decades, offers a captivating view of the emergence and development of an entirely new jewelry philosophy. Its way paved by a few forerunners, this philosophy has now taken hold worldwide among the avant-garde in the world of jewelry.

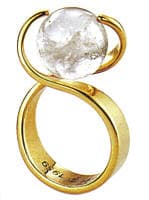

| Ring "spherical" by Friedrich Becker, 1959. 18 karat yellow gold, rock crysta | Pendant by Herbert Zeitner, approx. 1960. Gold, rock crystal, pearls |

| Brooch by Björn Weckström, 1965. Gold, tourmaline | |

At the hub of jewelry design in Germany and in collaboration with knowledgeable advisors, new tendencies in individual jewelry design were observed, promoted by means of exhibitions and design competitions, and documented during the creation of a museum collection of avant-garde works.

| Brooch by Anton Cepka, 1967. Fine silver, red, pink gemstone, probably tourmaline |

Contacts with galleries, collectors, and jewelry artists in Germany and abroad led to intensive dialogues with jewelry artists from Japan, Korea, Israel, Italy and Catalonia alongside those from Poland, Russia, and other countries. With more than 800 jewelry objects from a period spanning four decades (1960-1998), the modern collection of the Jewelry Museum of Pforzheim is one of the most extensive ever.

| Brooch by Fritz Maierhofer, 1972. Gold, acrylic glass |

Very few private collections, and hardly any public ones, can offer such a wide spectrum of works, with examples from 20 countries around the world. In the quality and scope of its collection, the museum can hold its own even among the greatest international collections, such as that of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

| Brooch by Claus Bury, 1972. 18 karat yellow gold, colored acrylic glass | Necklace by Daniel Kruger, 1976. Copper, silver parcel-gilt, silk, glass |

The modern collection shows how, since the 1950s, a new art of jewelry has been developing, nearly unnoticed except by experts and connoisseurs. Emerging from a few centers of activity, it has taken hold and shown individual influences in many countries and across entire continents, according to museum director and proven expert in the field Fritz Falk. One common outlook is that goldsmiths feel themselves to be artists, just as sculptors or painters are, who create individual works of art for the human body. This means that their creations are a reflection of artistic as well as social conditions. For the wearer, this kind of jewelry signifies identification and communication, because the piece becomes a challenge to all involved - designer, wearer, advisor - to enter into an intensive dialogue through the medium of jewelry. "Ornamentum humanum" was what Karl Schollmeyer, longtime director of the Kunst- and Werkkunstschule Pforzheim (Art and Artisan School of Pforzheim), called the new jewelry in his 1974 book.

| Bracelet by Sigurd Persson, 1980. Silver, red plastic |

The way in which the new art of jewelry strives to relate to people on an individual level, while at the same time taking part in the artistic developments and trends of our time, continues to inform our understanding of jewelry as a sign of the times. The tendency toward new materials was one of the earliest to take hold. Although numerous jewelry designers, such as Reinhold Reiling, Klaus Ullrich, Fritz Becker, Hermann Junger, Peter Skubic and others in Germany, David Watkins in the UK, Mario Pinton in Italy, Josef Symon in Austria, Arline Fisch in the US, Yasuki Hiramatsu in Japan, and Claus Bury, who was a guest instructor in the UK, Israel, Australia and the US taught successfully at academies and universities of applied sciences, very few schools were formed except for "Padua," according to the director of the Jewelry Museum of Pforzheim, Fritz Falk. Their influences, however, are clearly visible in the individual further developments of the generations that followed.

| Necklace by Wolfgang Lieglein, 1990/91. Papier máche, fabric, glass stones, plastics, metals, wood |

"Culture for everyone": the famous comment by the former head of the Culture Department of Frankfurt, Hilmar Hoffmann, aptly describes how the understanding of society and artists, also shown by contemporary jewelry, developed during the 1980s. It was at precisely this time that many new galleries were founded to focus exclusively on one-of- a-kind contemporary jewelry pieces. At the same time, the gallery owners themselves are often jewelry designers. Two of the Jewelry Museum's exhibitions are an expression of the emergence of art and culture from a shadowy existence into a lively scene open to the public. If the "Tendenzen"-Exhibition (Trend Show) of 1982 did not yet fully focus on jewelry made by the international avant-garde, the Ornamenta I, in 1989, heralded the effort to make jewelry into a cultural and social experience.

| Ring by Mario Pinton, 1982. 18 karat yellow gold, ruby |

The tendencies of the 1990s might be summarized as a return to the roots of the trade, with an evident return to the actual craft. After earlier experiments with materials and large-dimension jewelry objects that dominated the body, the ornamental aspects of jewelry and precious metals were rediscovered.

| Ring by Giampaolo Babetto, 1982. 18 karat yellow gold |

The final decade of the last century is not characterized by any definite direction. Everything is possible, everything is allowed: the great diversity of materials is accompanied by a less inhibited treatment of kitsch and fashion. Irony and humor also appear more frequently in these works.

The great battle to be recognized as art is over. In its wake, creative design is allowed new freedom to use a wide spectrum of materials and to combine them. New jewelry pieces are created and develop their own values through their relationship to the wearer, and in connection with his or her memories and associations.

| Fritz Falk, "European Jewellery 1840-1940" From the Collection of the Jewelry Museum of Pforzheim. 2003 |